Dead of Night; horror, UK, 1945; D: Cavalcanti, Charles Crichton, Basil Dearden, Robert Hamer, S: Mervyn Johns, Roland Culver, Sally Ann Howes, Anthony Baird, Ralph Michael

Walter Craig is plagued by nightmares. He stops his car at a country house because it remainds him of a dream he had. He enters and meets six people there - and recognizes them all from his dream, and - although his memory is sketchy - predicts that something awful is going to happen when the lights go off. The guests then start telling horror stories to make the time pass by: Hugh remembers how he dreamt of a driver of a death coach, recognized him the next day in a bus, thus refused to enter and then the bus had a crash; Sally remembers an eerie Christmas party; Mr. Cortland recounts how he got a mirror which reflected him in a foreign room; two golfers compete for a girl, one of them cheats and thus the order commits suicide by walking in the lake, and then haunts the first golfer as a ghost; ventriloquist Maxwell kills a man for suspecting him of stealing his dummy. As the lights go off, Walter kills a man in the house, and enters a nightmare where he is in prison, getting chocked by the dummy. Finally, he awakens from his nightmare - and drives to the house again, not remembering anything.

An anthology of five stories, all framed by a sixth, "Dead of Night" achieved cult status for being one of early British horror films, but holds up surprisingly well even today. The quality differs for each story, some are weaker (the Christmas party), one is good, albeit pure comedy (the golf story), yet at least one managed to rise to the occassion and deliver an all-time classic, inspired horror highlight: the one where Mr. Cortland gets a mirror in his bedroom - but sees himself in a foreign, castle-like room in the reflection, which casuses a high spark of mystery, uncertainty and suspense, since the viewers are aware something is "off", but cannot quite put their finger on it until the great pay-off. The 2nd best story is the one involving the driver of a death coach, while the most famed and popular story became the ventriloquist episode, even though its potentials involving the dummy could have been used to a much better level ("Chucky", for instance, showed where this could have went). A saving grace is given overall by a fantastic, scary and expressionistic "nightmare" twist ending, which aligns everything in a harmonius whole and makes sure that the viewers get a worthy pay-off for waiting so long.

Grade;+++

Tuesday, May 31, 2016

Sunday, May 29, 2016

Saint Seiya (Arc 1-4)

Saint Seiya; animated fantasy action series, Japan, 1986; D: Kozo Morishita, S: Toru Furuya, Ryo Horikawa, Hirotaka Suzuki, Keiko Han, Hideyuki Hori

Seiya is a teenage orphan who was trained ever since he was a kid by Marin to become a Saint, a warrior with special powers who will protect Kaori, who is the embodiment of the Goddess of Athena. By defeating others in a match in Greece, Seiya manages to obtain the Pegasus cloth, and thus qualifies to participate in a match involving other Saints who all compete to get an even higher cloth, the Gold cloth. He makes friend with other Saints—Dragon Shiryu, Andromeda Shun, Cygnus Hyouga and even Shun's brother, Phoenix Ikki, who almost became evil. The match is interrupted, however, when parts of the Gold cloth are stolen by the minions of Arles, the new, corrupt governor of the Sanctuary, who wants to rule the world. The Saints thus fight him.

Once one of the most popular anime shows from the 80s, that was even awarded the 1st place in the Animage magazine, hyped "Saint Seiya" lost a lot of its initial charm today and was corroded by time since it spent too much energy on generic action and too little on characters or the much more appealing mysticism surrounding its background based on Greek mythology. There are a lot of problems when one story starts four times (first when Seiya fights to get the Pegasus cloth; second when Pegasus Seiya fights in the tournament match; third when the Saints need to convert Ikki to the good side; fourth when they search for the stolen Gold cloth). It stacks a lot of illogical moments or inconsistencies—why are the teenage protagonists fighting to get the Gold cloth when they do not even know what it is? Why were they sent to train for almost a decade on desolate places around the world, instead of just training together, as friends, in proximity, to keep contact? Why didn't human rights NGOs intervene for child abuse?—as well as featuring the good side, the Graude Foundation, that is so shady and has such questionable methods that one almost wonders if they are evil as well—this is especially obvious in the misguided premise in which orphans are taken away by this organization and taught to train to fight since the age of 10, which reminds too much of child soldier recruitment. However, there are some iconic images here (for instance, the design of the Sanctuary; episode 23 recounts how the Golden Cloth was invoked to cause the fall of Napoleon, the Mongol and the Roman Empire because they caused too much suffering to humanity).

"Saint Seiya" was initially presented as a 'soft' version of "Fist of the North Star", yet unfortunately underwent a "Dragonball-ization" fairly quickly and proved that it is basically just a "fightorama" anime for the testosterone charged viewers who get a thrill out of endless battles between the warriors of good and evil, with several brutal moments which are strangely bloody (especially episodes 16, 28 and 31). No matter how great action sequences are, they can only go so far—and the action sequences here are only sporadically impressive, anyway. While Seiya seems sympathetic, he—and every other character—is only shown fighting, and thus remained one-dimensional, without charm, wit, humor or any versatile emotional development. That is why the protagonists' loyalty never seems genuine, since they are not shown doing anything together privately to bond. By narrowing the storyline down to only battle and fight clashes, which are always predictable (a bad guy boasts how the puny Seiya can never defeat him—and then Seiya defeats him), "Saint Seiya's" narrative range remained thin, bland and monotone. And suitable for never ending array of shallow battles, with such silly scenes as Hyouga fighting polar bears or Shiryu kicking a waterfall until it flows upwards. The only interesting battle technique was presented with Andromeda Shun, who allows his sentient, very long chain to make a circle around him on the floor, and then waits to stab the enemy as soon as he steps into this area. It is too little for a great moment to compensate for 10 insipid episodes, but the first 4 arcs of "Saint Seiya" have two truly magical, enchanting moments that stand out precisely because they are superior to the rest of the average events. Actually, they are so great one almost feels sadness that they were not in a better story, since they are precious. One is episode 26, when one bad guy was defeated, but Athena starts to glow, approaches him and forgives him, and he has a blissful expression on his face before dying, almost as if he found his inner peace. The other is in episode 13, when Dragon Shiryu is wounded, but decides to risk his life fighting Black Dragon warrior in order to protect friend Seiya. After the battle, Shiryu is bleeding, slowly dying, but then Black Dragon shows up—and instead of finishing him off, he actually uses his finger to heal him, take his wounds, and die instead—with his final words being: "... I also want to believe... in your so-called friendship!" This has such pathos that it is even comparable to the finale in "Blade Runner"—but alas, it remained in minority in this storyline.

Grade;+

Once one of the most popular anime shows from the 80s, that was even awarded the 1st place in the Animage magazine, hyped "Saint Seiya" lost a lot of its initial charm today and was corroded by time since it spent too much energy on generic action and too little on characters or the much more appealing mysticism surrounding its background based on Greek mythology. There are a lot of problems when one story starts four times (first when Seiya fights to get the Pegasus cloth; second when Pegasus Seiya fights in the tournament match; third when the Saints need to convert Ikki to the good side; fourth when they search for the stolen Gold cloth). It stacks a lot of illogical moments or inconsistencies—why are the teenage protagonists fighting to get the Gold cloth when they do not even know what it is? Why were they sent to train for almost a decade on desolate places around the world, instead of just training together, as friends, in proximity, to keep contact? Why didn't human rights NGOs intervene for child abuse?—as well as featuring the good side, the Graude Foundation, that is so shady and has such questionable methods that one almost wonders if they are evil as well—this is especially obvious in the misguided premise in which orphans are taken away by this organization and taught to train to fight since the age of 10, which reminds too much of child soldier recruitment. However, there are some iconic images here (for instance, the design of the Sanctuary; episode 23 recounts how the Golden Cloth was invoked to cause the fall of Napoleon, the Mongol and the Roman Empire because they caused too much suffering to humanity).

"Saint Seiya" was initially presented as a 'soft' version of "Fist of the North Star", yet unfortunately underwent a "Dragonball-ization" fairly quickly and proved that it is basically just a "fightorama" anime for the testosterone charged viewers who get a thrill out of endless battles between the warriors of good and evil, with several brutal moments which are strangely bloody (especially episodes 16, 28 and 31). No matter how great action sequences are, they can only go so far—and the action sequences here are only sporadically impressive, anyway. While Seiya seems sympathetic, he—and every other character—is only shown fighting, and thus remained one-dimensional, without charm, wit, humor or any versatile emotional development. That is why the protagonists' loyalty never seems genuine, since they are not shown doing anything together privately to bond. By narrowing the storyline down to only battle and fight clashes, which are always predictable (a bad guy boasts how the puny Seiya can never defeat him—and then Seiya defeats him), "Saint Seiya's" narrative range remained thin, bland and monotone. And suitable for never ending array of shallow battles, with such silly scenes as Hyouga fighting polar bears or Shiryu kicking a waterfall until it flows upwards. The only interesting battle technique was presented with Andromeda Shun, who allows his sentient, very long chain to make a circle around him on the floor, and then waits to stab the enemy as soon as he steps into this area. It is too little for a great moment to compensate for 10 insipid episodes, but the first 4 arcs of "Saint Seiya" have two truly magical, enchanting moments that stand out precisely because they are superior to the rest of the average events. Actually, they are so great one almost feels sadness that they were not in a better story, since they are precious. One is episode 26, when one bad guy was defeated, but Athena starts to glow, approaches him and forgives him, and he has a blissful expression on his face before dying, almost as if he found his inner peace. The other is in episode 13, when Dragon Shiryu is wounded, but decides to risk his life fighting Black Dragon warrior in order to protect friend Seiya. After the battle, Shiryu is bleeding, slowly dying, but then Black Dragon shows up—and instead of finishing him off, he actually uses his finger to heal him, take his wounds, and die instead—with his final words being: "... I also want to believe... in your so-called friendship!" This has such pathos that it is even comparable to the finale in "Blade Runner"—but alas, it remained in minority in this storyline.

Grade;+

Thursday, May 26, 2016

Super Fuzz

Poliziotto superpiu; comedy, Italy / Spain / USA 1980; D: Sergio Corbucci, S: Terence Hill, Ernest Borgnine, Joanne Dru, Julie Gordon

Dave Speed in an ordinary police officer, up until a rocket explodes over him, and contaminates the area with strange radiation. However, much to the surprise of his superior, Sergeant Dunlop, Dave returns unharmed - and with super powers: he is invincible, has superhuman strength and telekinesis. He uses these powers to solve some crimes cases, but quickly figures out that he loses those powers as soon as something red is near him. When a mafia boss figures Dave is too dangerous, and that he might expose his plan for smuggling of forged money in fish, he frames Dave with murder of Dunlop. Dave is sentenced to death, but escapes due to his powers, saves Dunlop and proves his innocence when he apprehends the bad guys.

Following the success of his heavy films, such as "Django" and "The Great Silence", director Sergio Corbucci decided to relax a bit and direct a few care-free comedies, among them two Spencer-Hill films, "A Friend is a Treasure" and "Odds and Evens". However, just like in these aforementioned films, and in kids-comedy "Super Fuzz" (somewhere also translated as "Super Cop"), where Terence Hill stars 'solo', Corbucci seems to have relaxed a tad too much, forgetting to insert any effort or wit into them, and just delivering a standard, conventional, albeit easily watchable flicks. The potential of a super-cop was wasted too much only on silly and lame jokes, such as Dave catching a speeding bullet with his teeth or Dunlop falling so hard on Dave that the ground beneath them collapses and they land on the other side of Earth, in Asia, or on too much empty walk, since the story (and jokes) are very thin. Still, veteran comedian Hill manages to squeeze a few charming moments, nonetheless, thanks to at least a few good jokes (one of the best is when he uses his telekinesis to control the billiard balls and win a bet against a thug in a pool billiard game or the unusual sequence where he is running as fast as a car and talking to the driver), which are welcomed, whereas one can at least admire the audacity of the Italian cinema for at least trying to create something different for the viewers than the usual.

Grade;+

Dave Speed in an ordinary police officer, up until a rocket explodes over him, and contaminates the area with strange radiation. However, much to the surprise of his superior, Sergeant Dunlop, Dave returns unharmed - and with super powers: he is invincible, has superhuman strength and telekinesis. He uses these powers to solve some crimes cases, but quickly figures out that he loses those powers as soon as something red is near him. When a mafia boss figures Dave is too dangerous, and that he might expose his plan for smuggling of forged money in fish, he frames Dave with murder of Dunlop. Dave is sentenced to death, but escapes due to his powers, saves Dunlop and proves his innocence when he apprehends the bad guys.

Following the success of his heavy films, such as "Django" and "The Great Silence", director Sergio Corbucci decided to relax a bit and direct a few care-free comedies, among them two Spencer-Hill films, "A Friend is a Treasure" and "Odds and Evens". However, just like in these aforementioned films, and in kids-comedy "Super Fuzz" (somewhere also translated as "Super Cop"), where Terence Hill stars 'solo', Corbucci seems to have relaxed a tad too much, forgetting to insert any effort or wit into them, and just delivering a standard, conventional, albeit easily watchable flicks. The potential of a super-cop was wasted too much only on silly and lame jokes, such as Dave catching a speeding bullet with his teeth or Dunlop falling so hard on Dave that the ground beneath them collapses and they land on the other side of Earth, in Asia, or on too much empty walk, since the story (and jokes) are very thin. Still, veteran comedian Hill manages to squeeze a few charming moments, nonetheless, thanks to at least a few good jokes (one of the best is when he uses his telekinesis to control the billiard balls and win a bet against a thug in a pool billiard game or the unusual sequence where he is running as fast as a car and talking to the driver), which are welcomed, whereas one can at least admire the audacity of the Italian cinema for at least trying to create something different for the viewers than the usual.

Grade;+

Wednesday, May 18, 2016

The Great Illusion

La Grande Illusion; war drama, France 1937; D: Jean Renoir, S: Jean Gabin, Pierre Fresnay, Marcel Dalio, Erich von Stroheim, Dita Parlo

World War I. French military officers—upper class aristocrat de Boëldieu; the wealthy middle class Rosenthal and working class Marechal—are captured on the western front by the German army and sent to a prisoner-of-war camp. They spend their time there slowly digging a tunnel in order to flee, but just as they are about to finish, they are transferred to a new camp. There Boëldieu finds a friend in the German general Rauffenstein, who connects with him because he is himself an aristocrat. Boëldieu stages a show for the soldiers while running away, so that Marechal and Rosenthal can escape while nobody is watching them. Boëldieu reckoned that Rauffenstein would allow him to escape - but to his surprise, Rauffenstein shoots him. Marechal and Rosenthal hide inside a farm of a widowed German woman, Elsa, and continue on foot until they reach the neutral Switzerland.

A war film without a single war sequence, "The Great Illusion" is arguably Jean Renoir's finest film, a humble—and very humane—classic of French cinema that also slyly showed a 'class war' which surpasses the ordinary conflict of two militaries: even though they are on two opposing sides, German warden of the camp, Rauffenstein, politely invites French prisoner Boëldieu to his office, because they are both aristocrats, whereas a similar thing is mirrored when the working-class Marechal is losing his mind in the solitary confinement, but a German working-class soldier shows solidarity and tries to comfort him, even later defending Marechal in front of another German soldier ("Why is that man crying?" - "...He is crying because the war is lasting for too long..."). However, despite this solidarity among classes, in the end the new "class", the nation, overrides in Europe of the 20th century. Renoir rises to the occasion and directs the film in a remarkably elegant way—just like Dostoevsky, he makes the story flow fluently despite a very long running time thanks to a careful depiction of characters, their personalities and their interactions, all adding to a bigger picture of a time and society, in this case the symbolic extinction of aristocracy in modern times. The film offers wonderful writing—from Boëldieu's comic remark "A tennis court is for tennis. A prison camp is for escaping", up to the widowed Elsa, who gives one of the greatest anti-war quotes of all times, when she points at the photo of her dead husband and her dead brothers, who all died in the war, and bitterly (and cynically) describes their deaths as "our greatest victories" in war. Renoir delivered an excellent, unassuming little film, whereas he gathered great actors, from Jean Gabin up to Erich von Stroheim as the compassionate German general Rauffenstein, thereby avoiding black-and-white depictions—whereas he even adds a few metafilm touches, since film critic Rob Hill observed how Renoir tried to keep the people in the same frame, thereby giving them equal status.

Grade;+++

World War I. French military officers—upper class aristocrat de Boëldieu; the wealthy middle class Rosenthal and working class Marechal—are captured on the western front by the German army and sent to a prisoner-of-war camp. They spend their time there slowly digging a tunnel in order to flee, but just as they are about to finish, they are transferred to a new camp. There Boëldieu finds a friend in the German general Rauffenstein, who connects with him because he is himself an aristocrat. Boëldieu stages a show for the soldiers while running away, so that Marechal and Rosenthal can escape while nobody is watching them. Boëldieu reckoned that Rauffenstein would allow him to escape - but to his surprise, Rauffenstein shoots him. Marechal and Rosenthal hide inside a farm of a widowed German woman, Elsa, and continue on foot until they reach the neutral Switzerland.

A war film without a single war sequence, "The Great Illusion" is arguably Jean Renoir's finest film, a humble—and very humane—classic of French cinema that also slyly showed a 'class war' which surpasses the ordinary conflict of two militaries: even though they are on two opposing sides, German warden of the camp, Rauffenstein, politely invites French prisoner Boëldieu to his office, because they are both aristocrats, whereas a similar thing is mirrored when the working-class Marechal is losing his mind in the solitary confinement, but a German working-class soldier shows solidarity and tries to comfort him, even later defending Marechal in front of another German soldier ("Why is that man crying?" - "...He is crying because the war is lasting for too long..."). However, despite this solidarity among classes, in the end the new "class", the nation, overrides in Europe of the 20th century. Renoir rises to the occasion and directs the film in a remarkably elegant way—just like Dostoevsky, he makes the story flow fluently despite a very long running time thanks to a careful depiction of characters, their personalities and their interactions, all adding to a bigger picture of a time and society, in this case the symbolic extinction of aristocracy in modern times. The film offers wonderful writing—from Boëldieu's comic remark "A tennis court is for tennis. A prison camp is for escaping", up to the widowed Elsa, who gives one of the greatest anti-war quotes of all times, when she points at the photo of her dead husband and her dead brothers, who all died in the war, and bitterly (and cynically) describes their deaths as "our greatest victories" in war. Renoir delivered an excellent, unassuming little film, whereas he gathered great actors, from Jean Gabin up to Erich von Stroheim as the compassionate German general Rauffenstein, thereby avoiding black-and-white depictions—whereas he even adds a few metafilm touches, since film critic Rob Hill observed how Renoir tried to keep the people in the same frame, thereby giving them equal status.

Grade;+++

Sunday, May 15, 2016

The Breakfast Club

The Breakfast Club; comedy / drama, USA, 1985; D: John Hughes, S: Emilio Estevez, Judd Nelson, Molly Ringwald, Anthony Michael Hall, Ally Sheedy, Paul Gleason

Five different high school students are sent to endure a detention in school at Saturday. Using the absence of their supervisor, Richard, the decide to communicate to each other: Claire comes from a wealthy family; Andrew is a wrestler who was punished for doing a prank to a helpless kid; intelligent Brian was busted for having a gun in his locker, since he wanted to commit suicide after getting an F; Allison is an outsider, and wears black; Bender is an aggressive kid who bullies everyone and was punished for pushing the fire alarm button. Despite their initial clash, especially towards Bender, the five teenagers gradually find common ground and grow in the process. After the end of the day, Bender and Claire decide to become a couple.

Director John Hughes' 2nd feature length film may just be his most widely recognised and popular one: "The Breakfast Club" uses his often stylistic choice of narrowing the time frame of the story to only one day, and - despite playing out only between five teenagers sitting during detention in school - contains a remarkably fluent story flow, which blend both relaxed comedy (Bender's remark to Richard's outfit: "Does Barry Manilow know you raid his wardrobe?"; Allison is so bored that she ties a thread around her index finger, and amusingly watches its lack of circulation turn blue for a while) and a more poignant character study with more dramatic moments in the second half - the highlight there is definitely Andrew's 4-minute long confession speech, in which he regrets his shameful prank against a helpless kid, while the camera slowly circles around him, which is virtuoso done and filmed in one take.

Hughes treats the teenage protagonists with a lot of respect and understanding, and avoids some cliches of the genre, thereby creating some wonderful characters, from the outcast Allison who wears black up to the gentle Claire. They also mirror some of teenage fears of growing up, especially the fear that they will lose some of their personality and innocence in the process, summed up brilliantly by Allison's quote: "When you grow up, your heart dies". However, these emotions are somewhat contaminated and ruined through the misguided character of Bender, who bullies everyone - a big mistake is that the movie missed a golden opportunity to have him actually undergo a transformation and regret his aggressive behaviour as much as it was done in Andrew's speech, since the fact that Claire would all of a sudden fall in love with him in the last 5 minutes of the film seems fake and sudden - as well as the disproportionate decision to put all the blame of all the problems of the five teenagers exclusively on their parents, whereas Hughes once again shows an uneven tendency to portrait the storyline in black and white (the grown ups, embodied in Richard, are treated negatively, whereas some of the teenagers, especially Bender, are white-washed and treated with apologetics), yet he still managed to craft a small, unassuming cult film which stood the test of time.

Grade;++

Five different high school students are sent to endure a detention in school at Saturday. Using the absence of their supervisor, Richard, the decide to communicate to each other: Claire comes from a wealthy family; Andrew is a wrestler who was punished for doing a prank to a helpless kid; intelligent Brian was busted for having a gun in his locker, since he wanted to commit suicide after getting an F; Allison is an outsider, and wears black; Bender is an aggressive kid who bullies everyone and was punished for pushing the fire alarm button. Despite their initial clash, especially towards Bender, the five teenagers gradually find common ground and grow in the process. After the end of the day, Bender and Claire decide to become a couple.

Director John Hughes' 2nd feature length film may just be his most widely recognised and popular one: "The Breakfast Club" uses his often stylistic choice of narrowing the time frame of the story to only one day, and - despite playing out only between five teenagers sitting during detention in school - contains a remarkably fluent story flow, which blend both relaxed comedy (Bender's remark to Richard's outfit: "Does Barry Manilow know you raid his wardrobe?"; Allison is so bored that she ties a thread around her index finger, and amusingly watches its lack of circulation turn blue for a while) and a more poignant character study with more dramatic moments in the second half - the highlight there is definitely Andrew's 4-minute long confession speech, in which he regrets his shameful prank against a helpless kid, while the camera slowly circles around him, which is virtuoso done and filmed in one take.

Hughes treats the teenage protagonists with a lot of respect and understanding, and avoids some cliches of the genre, thereby creating some wonderful characters, from the outcast Allison who wears black up to the gentle Claire. They also mirror some of teenage fears of growing up, especially the fear that they will lose some of their personality and innocence in the process, summed up brilliantly by Allison's quote: "When you grow up, your heart dies". However, these emotions are somewhat contaminated and ruined through the misguided character of Bender, who bullies everyone - a big mistake is that the movie missed a golden opportunity to have him actually undergo a transformation and regret his aggressive behaviour as much as it was done in Andrew's speech, since the fact that Claire would all of a sudden fall in love with him in the last 5 minutes of the film seems fake and sudden - as well as the disproportionate decision to put all the blame of all the problems of the five teenagers exclusively on their parents, whereas Hughes once again shows an uneven tendency to portrait the storyline in black and white (the grown ups, embodied in Richard, are treated negatively, whereas some of the teenagers, especially Bender, are white-washed and treated with apologetics), yet he still managed to craft a small, unassuming cult film which stood the test of time.

Grade;++

Tuesday, May 10, 2016

Synecdoche, New York

Synecdoche, New York; drama / tragedy, USA, 2008; D: Charlie Kaufman, S: Philip Seymour Hoffman, Samantha Morton, Michelle Williams, Catherine Keener, Emily Watson, Dianne Wiest, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Hope Davis, Tom Noonan

Caden is a theatre director living in a small town. After a water pipe explodes in his face, he finds himself in a series of health problems. On top of all, his wife Adele leaves him with their daughter, Olive, and goes to Berlin. However, there is at least one good news for him: he gets a prestigious fellowship, and decides to use the money to go to New York and set up a revolutionary play - a one whose topic will be his own life, and a one he and his crew will work on for the next thee decades. As time goes by, and he is still working on his play, he encounters several personal tribulations - his failed relationship with Hazel, his failed marriage with actress Claire, his failed reconciliation with Olive, now a lesbian; the suicide of the actor who plays him in the play... - and decides to use it all in the play, a set which is constructed under a dome. Finally, now an old man, Caden asks an actress to take over his position as a director. The actress in return gives him the assignment to play her role on the set. Before he dies, he reconciles with the actresses' mother.

Charlie Kaufman's directorial debut film, "Synecdoche, New York" once again demonstrated all the best and worst from the writer: on one hand, he conjures up a remarkable concept, a one which is highly ambitious, and uses the most outlandish ideas as an allegory for today's state of human kind, but on the other hand, his narrative is so 'autistic' and his characters so joyless, astringent and anaemic that they almost nullify each other. Similarly like Pirandello's "Six Characters in Search of an Author", that contemplated how every art is a form of alternate reality, Kaufman here presents a story in which a theatre director crafts a play about his own life, or better said a play which will encompass human life as a whole, but just as he decides to create a megalomaniac project out of it, and construct a whole set in a dome for itself, Kaufman himself seems to be overburdened with a too pretentious overarching reach. Kaufman has a great point in the finale: it is very bitter, and very uncomfortable, and that is why many have rejected the film. However, no matter how unpleasant, a comment can still be true.

Here, the finale is depressive, but shows a brave message how every human is destined to be crushed by life, and how there is only one thing that unifies humanity - disappointment (the fantastic, albeit grim narration: "What was once before you - an exciting, mysterious future - is now behind you. Lived; understood; disappointing. You realize you are not special. You have struggled into existence, and are now slipping silently out of it. This is everyone's experience. Every single one..."). As much as someone tries to "capture" the entire life in art, and invest his whole lifetime in it, it is futile, since life will "outlive" that ambition. Life is more than one artist's lifetime. It is uncapturable. However, in order to get to that great finale, the viewer has to pave his way through a mass of empty walk, empty dialogues, pretentiousness, tedious and grey, melodramatic scenes. No matter how inspiring an ending is, it cannot compensate for absolutely every omission in the entire film up to it. No ending can. Many have reacted too negatively and dismissed the film completely. That is exaggerated and undue, since the ending has a point. Yet the whole first hour of the film is pointless. "Synecdoche" is not a 'Pyrrhic victory' - it is more like a 'Pyrrhic defeat': it succumbs to its own over-ambition, but uses even that as a cathartic synecdoche for human life in general.

Grade;++

Caden is a theatre director living in a small town. After a water pipe explodes in his face, he finds himself in a series of health problems. On top of all, his wife Adele leaves him with their daughter, Olive, and goes to Berlin. However, there is at least one good news for him: he gets a prestigious fellowship, and decides to use the money to go to New York and set up a revolutionary play - a one whose topic will be his own life, and a one he and his crew will work on for the next thee decades. As time goes by, and he is still working on his play, he encounters several personal tribulations - his failed relationship with Hazel, his failed marriage with actress Claire, his failed reconciliation with Olive, now a lesbian; the suicide of the actor who plays him in the play... - and decides to use it all in the play, a set which is constructed under a dome. Finally, now an old man, Caden asks an actress to take over his position as a director. The actress in return gives him the assignment to play her role on the set. Before he dies, he reconciles with the actresses' mother.

Charlie Kaufman's directorial debut film, "Synecdoche, New York" once again demonstrated all the best and worst from the writer: on one hand, he conjures up a remarkable concept, a one which is highly ambitious, and uses the most outlandish ideas as an allegory for today's state of human kind, but on the other hand, his narrative is so 'autistic' and his characters so joyless, astringent and anaemic that they almost nullify each other. Similarly like Pirandello's "Six Characters in Search of an Author", that contemplated how every art is a form of alternate reality, Kaufman here presents a story in which a theatre director crafts a play about his own life, or better said a play which will encompass human life as a whole, but just as he decides to create a megalomaniac project out of it, and construct a whole set in a dome for itself, Kaufman himself seems to be overburdened with a too pretentious overarching reach. Kaufman has a great point in the finale: it is very bitter, and very uncomfortable, and that is why many have rejected the film. However, no matter how unpleasant, a comment can still be true.

Here, the finale is depressive, but shows a brave message how every human is destined to be crushed by life, and how there is only one thing that unifies humanity - disappointment (the fantastic, albeit grim narration: "What was once before you - an exciting, mysterious future - is now behind you. Lived; understood; disappointing. You realize you are not special. You have struggled into existence, and are now slipping silently out of it. This is everyone's experience. Every single one..."). As much as someone tries to "capture" the entire life in art, and invest his whole lifetime in it, it is futile, since life will "outlive" that ambition. Life is more than one artist's lifetime. It is uncapturable. However, in order to get to that great finale, the viewer has to pave his way through a mass of empty walk, empty dialogues, pretentiousness, tedious and grey, melodramatic scenes. No matter how inspiring an ending is, it cannot compensate for absolutely every omission in the entire film up to it. No ending can. Many have reacted too negatively and dismissed the film completely. That is exaggerated and undue, since the ending has a point. Yet the whole first hour of the film is pointless. "Synecdoche" is not a 'Pyrrhic victory' - it is more like a 'Pyrrhic defeat': it succumbs to its own over-ambition, but uses even that as a cathartic synecdoche for human life in general.

Grade;++

Saturday, May 7, 2016

Sixteen Candles

Sixteen Candles; comedy, USA, 1984; D: John Hughes, S: Molly Ringwald, Anthony Michael Hall, Michael Schoeffling, Paul Dooley

Samantha has just turned 16. Unfortunately for her, her whole family, even her parents, forgot about her birthday since her older sister Ginny is preparing to get married tomorrow. In high school, Ted, a geek, is hitting on her since he finally wants to lose his virginity, but Samantha has a crush on Jake - but he is already dating Caroline. Samantha is annoyed that several relatives spend the night at her house for the wedding - including a Chinese exchange student, Dong. Jake dumps the drunk Caroline, and Ted uses the opportunity to parade with her in a car. After Ginny's wedding, Samantha talks to Jake and they fall in love.

John Hughes' directing career spans only seven years, and he only directed eight films in that period. The impression that he actually directed far more can thus be attributed to how almost every one of his films had a huge impact on the audience. His feature length debut film "Sixteen Candles" is one his lesser films, where he made a compromise by appealing too much to the wide audience and the niche of 'crazy teen-comedy', yet he still managed to fuse a few of his feelings which mirror the quiet anxiety and insecurity of teenagers growing up and trying to find their place in the world. The storyline is 'rough', and it seems that by trying to infuse as much wild jokes as possible involving the geek kid, Hughes forgot about his two protagonists in the process, Samantha and Jake - in the second half, for instance, the main heroine is absent for almost half an hour from the screen - which seems uneven, yet some of the jokes are simply hilarious anyway (while doing an anonymous "sex quiz" in school, Samantha arrives to the question: "Have you ever touched it?" and writes the reply: "Almost"; the 'politically incorrect' jokes of the Chinese exchange student Dong, especially in the scene where grandpa asks him: "Where... is my... auto-mobile?"; the moment where Samantha finds out that her grandparents will sleep in her room) and it seems that the author was getting the 'hang of it' as the movie went along, which all resulted in an offbeat comedy, which has just enough emotions and pathos to stand out from the rest of standard teen-comedies.

Grade;++

Samantha has just turned 16. Unfortunately for her, her whole family, even her parents, forgot about her birthday since her older sister Ginny is preparing to get married tomorrow. In high school, Ted, a geek, is hitting on her since he finally wants to lose his virginity, but Samantha has a crush on Jake - but he is already dating Caroline. Samantha is annoyed that several relatives spend the night at her house for the wedding - including a Chinese exchange student, Dong. Jake dumps the drunk Caroline, and Ted uses the opportunity to parade with her in a car. After Ginny's wedding, Samantha talks to Jake and they fall in love.

John Hughes' directing career spans only seven years, and he only directed eight films in that period. The impression that he actually directed far more can thus be attributed to how almost every one of his films had a huge impact on the audience. His feature length debut film "Sixteen Candles" is one his lesser films, where he made a compromise by appealing too much to the wide audience and the niche of 'crazy teen-comedy', yet he still managed to fuse a few of his feelings which mirror the quiet anxiety and insecurity of teenagers growing up and trying to find their place in the world. The storyline is 'rough', and it seems that by trying to infuse as much wild jokes as possible involving the geek kid, Hughes forgot about his two protagonists in the process, Samantha and Jake - in the second half, for instance, the main heroine is absent for almost half an hour from the screen - which seems uneven, yet some of the jokes are simply hilarious anyway (while doing an anonymous "sex quiz" in school, Samantha arrives to the question: "Have you ever touched it?" and writes the reply: "Almost"; the 'politically incorrect' jokes of the Chinese exchange student Dong, especially in the scene where grandpa asks him: "Where... is my... auto-mobile?"; the moment where Samantha finds out that her grandparents will sleep in her room) and it seems that the author was getting the 'hang of it' as the movie went along, which all resulted in an offbeat comedy, which has just enough emotions and pathos to stand out from the rest of standard teen-comedies.

Grade;++

Friday, May 6, 2016

7 Grandmasters

Hu bao long she ying; martial arts, Taiwan, 1977; D: Joseph Kuo, S: Yi-Min Li, Jack Long, Mark Long, Nancy Yen

After a note that he is not the best, Sang Kuan Chun, an old kung fu master, decides to prove otherwise before retiring by fighting each of the seven kung fu grandmasters. He takes three students with him on the journey - and unwillingly a fourth one, Siu Ying, who begs him to train him. Master Chun manages to defeat all of the grandmasters, and in the process Ying becomes his best student, after he proved his loyalty by taking care of the master after Chun caught a cold. However, a masked man misguides Ying into believing that Chun killed his father. Ying attacks and wounds Chun, but upon realizing he was tricked, he turns against the masked man and kills him.

"7 Grandmasters" is a proportionally well made martial arts film, popular in Asia's East at that time, that is somewhat ungainly and hastily assembled, yet still well made, which assured it cult status. Director Joseph Kuo leads a very straight-forward approach, and thus the narrative is simple and easy to follow, and is basically a 'swan song' for the old kung fu master who plans to retire as soon as he proves the maximum of his abilities one last time, whereas the mystery subplot involving a masked man who stole a part of his scripture was ranked high by critics and seen as refreshing addition in the kung fu lore, even though the ending resulting from it could have been far better derived. Of course, the highlights are definitely the seven battle and action sequences - even though they do not reach the level of J. Chan's "Police Story" or "Project A", they are meticulously choreographed (a student fighting Siu Ying while holding a cup of tea in his arm without spilling it; kung fu master Chun fighting an adversary without arms; Chun using the grappling hook of two swords of an opponent to jam them down on the floor with his bo...) and small crumbs of 'comic relief' were provided through the clumsy character of Siu Ying (especially when he is only left with eating the butt of a fried chicken during dinner in the open).

Grade;++

After a note that he is not the best, Sang Kuan Chun, an old kung fu master, decides to prove otherwise before retiring by fighting each of the seven kung fu grandmasters. He takes three students with him on the journey - and unwillingly a fourth one, Siu Ying, who begs him to train him. Master Chun manages to defeat all of the grandmasters, and in the process Ying becomes his best student, after he proved his loyalty by taking care of the master after Chun caught a cold. However, a masked man misguides Ying into believing that Chun killed his father. Ying attacks and wounds Chun, but upon realizing he was tricked, he turns against the masked man and kills him.

"7 Grandmasters" is a proportionally well made martial arts film, popular in Asia's East at that time, that is somewhat ungainly and hastily assembled, yet still well made, which assured it cult status. Director Joseph Kuo leads a very straight-forward approach, and thus the narrative is simple and easy to follow, and is basically a 'swan song' for the old kung fu master who plans to retire as soon as he proves the maximum of his abilities one last time, whereas the mystery subplot involving a masked man who stole a part of his scripture was ranked high by critics and seen as refreshing addition in the kung fu lore, even though the ending resulting from it could have been far better derived. Of course, the highlights are definitely the seven battle and action sequences - even though they do not reach the level of J. Chan's "Police Story" or "Project A", they are meticulously choreographed (a student fighting Siu Ying while holding a cup of tea in his arm without spilling it; kung fu master Chun fighting an adversary without arms; Chun using the grappling hook of two swords of an opponent to jam them down on the floor with his bo...) and small crumbs of 'comic relief' were provided through the clumsy character of Siu Ying (especially when he is only left with eating the butt of a fried chicken during dinner in the open).

Grade;++

Tuesday, May 3, 2016

Black Peter

Černý Petr; comedy, Czechia, 1964; D: Miloš Forman, S: Ladislav Jakim, Pavla Martinkova, Jan Vostrcil

After finishing school, youngster Petr does not know what he wants to do with his life. He finds a job as an observer and informal security guard against shoplifters in a store, but when he thinks a man stole something, Petr follows him, but is to indecisive to confront him. Petr brings a girl he likes to a dance hall, but is humiliated there by a teenage bully who borrows some money from him. In the end, Petr loses his job and is scorned by his father and mother at home.

Miloš Forman's feature length debut film is a too simplistic take on confused and indecisive youth trying to make it in the world of grown ups to really engage the viewers, since too many subplots and possibilities were left unexplored or underused. "Black Peter" attracted attention during its premiere for openly tackling the topic of the young generations feeling lost in the world, and using some cinematic techniques from the French new wave, which made it seem modern, yet all this was too meagre, whereas Forman still seemed indecisive himself, just like the title protagonist, evident in the "sudden" ending which seems as if it left a whole story out of the picture. The jokes are sometimes flat, except in the opening act (the prolonged, comical sequence where Petr follows a man suspect of stealing something from the shop, but is too indecisive to tell him anything, and thus just slowly walks behind him for a long time), whereas the storyline is thin, more suitable for a short film, though it is memorable for portraying Petr's overdominating parents who add "salt to the wound" at home by constantly criticizing him, and his dad (Jan Vostrcil) especially stands out, not only for his caprice of constantly holding his hands on his chest while standing.

Grade;++

After finishing school, youngster Petr does not know what he wants to do with his life. He finds a job as an observer and informal security guard against shoplifters in a store, but when he thinks a man stole something, Petr follows him, but is to indecisive to confront him. Petr brings a girl he likes to a dance hall, but is humiliated there by a teenage bully who borrows some money from him. In the end, Petr loses his job and is scorned by his father and mother at home.

Miloš Forman's feature length debut film is a too simplistic take on confused and indecisive youth trying to make it in the world of grown ups to really engage the viewers, since too many subplots and possibilities were left unexplored or underused. "Black Peter" attracted attention during its premiere for openly tackling the topic of the young generations feeling lost in the world, and using some cinematic techniques from the French new wave, which made it seem modern, yet all this was too meagre, whereas Forman still seemed indecisive himself, just like the title protagonist, evident in the "sudden" ending which seems as if it left a whole story out of the picture. The jokes are sometimes flat, except in the opening act (the prolonged, comical sequence where Petr follows a man suspect of stealing something from the shop, but is too indecisive to tell him anything, and thus just slowly walks behind him for a long time), whereas the storyline is thin, more suitable for a short film, though it is memorable for portraying Petr's overdominating parents who add "salt to the wound" at home by constantly criticizing him, and his dad (Jan Vostrcil) especially stands out, not only for his caprice of constantly holding his hands on his chest while standing.

Grade;++

Sunday, May 1, 2016

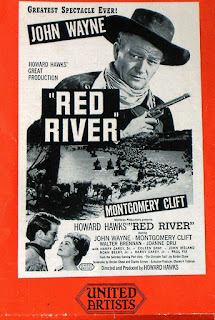

Red River

Red River; western / road movie, USA, 1948; D: Howard Hawks, S: John Wayne, Montgomery Clift, Walter Brennan, Joanne Dru

19th century. After losing the woman he loved in an Indian attack, cowboy Dunson and his friend, cook Groot, start a ranch in Texas with only a one cow and one bull. 14 years later, the civil war left the American south bankrupt, and thus Dunson decides to migrate his 9,000 head of cattle to Missouri to sell them for a better prize. The journey is 1,000 miles long, and he uses help from his adopted son Matt, as well as over a dozen cowboys who oversee the cattle column. During their long trip through the desert, Dunson proves to be an autocratic, harsh leader, who punishes deserters with killing, which culminates in a mutiny in which Matt takes over and re-directs the column towards the west, to Kanzas. There, Matt sells the heard and earns a fortune, but Dunson shows up to kill him for disobedience. However, thanks to Matt's girlfriend, Tess, Dunson forgives him.

Howard Hawk's first excursion into the western waters proved to be a lucky strike, since the director would helm four further westerns and collaborate with one of his favorite actors, John Wayne, more frequently. Even though the first 10-15 minutes could have been easily cut (Dunson just simply arrives at a piece of land and decides to annex it all for his cattle, and take it away from the owner, which seems ruffian), western-road movie "Red River" gains momentum once the main plot sets in, the long, 1,000 miles march of cowboys who are trying to transport their 9,000 cattle heard to Missouri, and this 'cattle Anabasis' really is a sight to behold at times in which Hawks uses his unobtrusive directing skills to conjure up a sense of adventure and awe, not only through the logistical challenges (the critics rightfully praised the dangerous sequence of cowboys trying to stop a cow stampede at night as a highlight) but also through character development of the migrating cowboys (Groot, who loses his false teeth in a poker game, for instance), who start to clash over the leadership of the rigid, stubborn Dunson, who's draconian methods alienate the workers since he wants everything to be done the 'hard way', ignoring the easy route. Some of Hawks' classic dialogues stand out ("There's three times in a man's life when he has a right to yell at the moon: when he marries, when his children come, and... when he finishes a job he had to be crazy to start."), and it was noteworthy that he demolished the 'John Wayne myth' by giving the actor a very complex role, very close to a bad guy - but, alas, "Red River" is ruined partially through a badly written role of Matt's love interest, Tess, and an ending which is no good, since it used a potential clash of Ford-ian tragedy and turned it into a strained, happy ending, though still resulting in a very good film with several highlights.

Grade;+++

19th century. After losing the woman he loved in an Indian attack, cowboy Dunson and his friend, cook Groot, start a ranch in Texas with only a one cow and one bull. 14 years later, the civil war left the American south bankrupt, and thus Dunson decides to migrate his 9,000 head of cattle to Missouri to sell them for a better prize. The journey is 1,000 miles long, and he uses help from his adopted son Matt, as well as over a dozen cowboys who oversee the cattle column. During their long trip through the desert, Dunson proves to be an autocratic, harsh leader, who punishes deserters with killing, which culminates in a mutiny in which Matt takes over and re-directs the column towards the west, to Kanzas. There, Matt sells the heard and earns a fortune, but Dunson shows up to kill him for disobedience. However, thanks to Matt's girlfriend, Tess, Dunson forgives him.

Howard Hawk's first excursion into the western waters proved to be a lucky strike, since the director would helm four further westerns and collaborate with one of his favorite actors, John Wayne, more frequently. Even though the first 10-15 minutes could have been easily cut (Dunson just simply arrives at a piece of land and decides to annex it all for his cattle, and take it away from the owner, which seems ruffian), western-road movie "Red River" gains momentum once the main plot sets in, the long, 1,000 miles march of cowboys who are trying to transport their 9,000 cattle heard to Missouri, and this 'cattle Anabasis' really is a sight to behold at times in which Hawks uses his unobtrusive directing skills to conjure up a sense of adventure and awe, not only through the logistical challenges (the critics rightfully praised the dangerous sequence of cowboys trying to stop a cow stampede at night as a highlight) but also through character development of the migrating cowboys (Groot, who loses his false teeth in a poker game, for instance), who start to clash over the leadership of the rigid, stubborn Dunson, who's draconian methods alienate the workers since he wants everything to be done the 'hard way', ignoring the easy route. Some of Hawks' classic dialogues stand out ("There's three times in a man's life when he has a right to yell at the moon: when he marries, when his children come, and... when he finishes a job he had to be crazy to start."), and it was noteworthy that he demolished the 'John Wayne myth' by giving the actor a very complex role, very close to a bad guy - but, alas, "Red River" is ruined partially through a badly written role of Matt's love interest, Tess, and an ending which is no good, since it used a potential clash of Ford-ian tragedy and turned it into a strained, happy ending, though still resulting in a very good film with several highlights.

Grade;+++

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)